Nostrum Essentia

Interview with

James Wines

James Wines is an American artist and architect. During the 50s and 60s, Wines worked as a plastic artist in Italy, where he exhibited his sculptures in galleries and corporate plazas. His time in this European country had a great influence on the development of his work, and the disciplinary cross over between this and architecture, art and the public space. Wines moved to New York where he began to build a career more focused on sustainable architecture and design. In 1970, together with Alison Sky, Emilio Sousa and Michelle Stone, he founded the design studio SITE.

SITE focuses on the sustainable design of buildings, public spaces and the integration of these in the context, seeking the fusion between art and architecture. Wines has been the recipient of a large number of awards, and since 1999 he has had a strong presence in academia, as a professor at Pennsylvania State University. Among his most recognized works is GHOST PARKING LOT, in Hamden, USA and the design of several BEST stores in Houston. In addition, he has published various texts, among which is Green Architecture, in 2000.

Interview by Mauricio Quirós (MQ), Fredy Massad (FM) and Álvaro Rojas (AR)

ECONOMY OF MEANS:

DOING LESS IN THESE TRYING TIMES

This conversation with James Wines might lead us to think back to some of the most essential parts of 20th century’s architecture. A side of the story often intentionally forgotten by the orthodox views of “Official History”, which struggles to deal with its radicality, heterodoxy and desire to defy any established terms.

Working from SITE (Sculpture in the Environment), Wines determinedly crossed the borders set out by academic rules throughout the 70’s and 80’s in order to play with art and concepts.. His main obsession was dematerializing the architectural object, de-architecturalizing it in a creative and unprejudiced way.

He was clearly influenced by Venturi, and also by some of the best bits of Marcel Duchamp, from whom he borrowed the title NOT SEEN and/or LESS SEEN of… in order to state: “Duchamp has been a key influence not just for painters and sculptors, but also for architects. He showed that every object, beyond its materiality, can be a concept, a traffic light that changes the viewer’s habits in respect of the context’’

The current speed of things tends to leave behind people that have been instrumental in creating the conceptual corpus of the present time. Speaking again with these people is a way to remember and reinforce the value and energy of their work, which has never gone astray.

Mauricio Quirós (MQ)- James, your practices in art and architecture already span over five decades and they have seen – certainly survived and thrived - many of the western world’s most severe crises; 1968, Vietnam, the Oil Crisis, the fall of the Iron Curtain, 9/11, 2008's financial crisis, Hurricane Katrina, you name them. What feels similar, or different, from those critical moments when compared to the crises that beset us today? What opportunities do you think they presented to your work?

James Wines (JM)- The one thing I think made SITE’s work unique in those circumstances was that there was always some kind of contextual, environmental commentary happening. Something was always talking about something. Most buildings are about form and space and structure and function and so forth, and that is part of it. But historically, buildings carried messages, they talked to people. All of our projects are relatively small compared to what they have done to the world. I have always been interested in, and practiced with, economy of means; that is, perform communication or create narrative structures in things with the variable of effort and money. It is about creating something that deals with people’s attitudes, something that they already brought to a site, some kind of information, some kind of expectations.

I have always been proud of the work SITE did with the BEST shops. We looked around and found situations, found objects, that were the perfect vehicle for these projects. A chair or a table or a shopping center, they all come with their own invested information, everyone knows what to expect. But if you invert and change that expectation, somewhat it generates a lot more dialogue with people. I always say that the highest compliment I got through the years was "I never thought about a building like that before." There were a lot of resources that I was using that were not from the fields of art or architecture and I still get much controversy because of these projects. Fifty years later I still get hostile remarks like "that is not art" or "that is not real architecture," as if there was something sacred that is real and I am just an artificial person doing artificial work.

I was in a conference many years ago with artists who launched their careers in the midst of hostile perceptions. It was an incredible event; Claes Oldenburg was involved, Frank Stella was there with his pinstriped painting set, Roy Lichtenstein... it was a group of people whose careers had been launched from hostility. When Roy Lichtenstein had his first show at the USA, Castelli and the New York Times published an article titled ‘Is this the worst artist in the world?’ I more or less started my career the same way.

BEST FOREST BUILDING, RICHMOND, VA 1979

BEST FOREST BUILDING, RICHMOND, VA 1979

But I have been very fortunate to have good art collectors as clients, they h courageous. I remember when I had a meeting with Sydney Lewis, a client, and he brought in the representatives of his company because he thought he should let them know what he was planning to do. Every one of them said "if you build a building like that, no one will go in it. A building like that will drive us to bankruptcy." At the end of the meeting, Sydney whispered “James, stay a little longer, I want to talk to you." As soon as all his colleagues left, he said "OK, James, when do we get started?" He clearly had a broader vision than his colleagues.

Going back to what I mean by economy of means I must say that when I start something, I try to think "how can I do this in the simplest way?" Again, SITE has had quite a big influence with a lot of other work that has been done. But I have noticed that almost every time someone tries to elaborate on it, they just make everything more complicated. It seems always less about the essence of the idea and more about formalism. I have even found buildings called and designed like High-rise of Homes, our project. What they often do is design a façade with lots of details to look more homey, more accommodating, more like a house. My idea was the total opposite. You would build a matrix and then let the people fill it like a collage. The result would be more arbitrary, more spontaneous, more reflective of the residents. It is economy of means but a completely different way of doing it, a whole different point of view. Today developers have a lot of money and want to make buildings using unlimited material resources and computing power. They seem to think things like “if I make my building with a lot of undulations, everybody will notice it.” But they do not. When you think about it, all buildings nowadays are undulated and are not distinctive anymore. Interestingly, art is different. At least my view of art is very different. I was a sculptor and I spent ten years from my early life making shapes and volumes, looking at it as though that was the end in art. I was perfectly successful as a sculptor until I met Frederick John Kiesler, the famous Austrian architect, who kept saying that he liked my architectural inclinations, even in sculpture. He was a mentor to many artists. He was not only an incredible brain; he was a real conceptual architect in the fullest sense

MQ- Before we started the conversation, you mentioned that you had a long friendship with artist Gordon Matta-Clark, and that you both developed works rooted on the idea of economy of means. You argued, however, that you approached it from completely opposite directions, even if both arrived at similar places. Can you elaborate on that?

JW- I would say I emerged from the environmental art movement. I was living in SoHo and every environmental artist lived on my street or the street after. And it was SoHo because it was all very cheap loft spaces. Believe it or not, I rented a five thousand square feet loft on Queen Street for $200 a month. All the manufacturing was moving out of Manhattan and there were these vacant lofts that nobody was supposed to live in them, but we did. And the more and more artists took advantage of those spaces, the more opportunities to work on a bigger scale and show your own work in your loft or the street. Artists began to take their works to the streets and questioned why show their work only on little precious art galleries. That is exactly what Duchamp violated, he violated your expectations. If you walk into an art gallery and there is a urinal sitting on a stand, you have to question where you are. Is that art? Or is that not art? Is this an art gallery? Or is this not an art gallery? It was Duchamp who set up that questioning factor. And that was what I think all environmental artists were doing. We were setting up a questioning factor. Why not use the streets? Why not use the landscape? Why not use another context? Why depend on art galleries to compete?

To your question, I think Gordon was working from a particular interest in buildings, and I started working from an interest in context. I, for example, was working with an audience and went to the kind of junk world. Gordon went to the suburban world or the factory world. But there were lots of people with similar attitudes. For example, Bob Smithson went to the land and the water. All of us had an objective that could not be developed in, or for, an art gallery. I always say that Ghost Parking Lot, a very early project, could not be taken away from its context without a total loss of meaning. You could put pictures in an art gallery, that was all you could do. But you could not put the art itself. It was totally intrinsic to the context. A parking lot of cars asphalted over is not only a commentary on fossil fuel and cars and everything else, but it is also a kind of art that you cannot put anyplace else. So that was the way we all got started. Almost every artist today is working with context in some way, they are really making context. I am glad that I was part of that beginning and the fact that we did it with great economy of means and, in some cases, combined with ecological interests. I think we did a lot of things that made of this economy of means a good precedent, something that should be continued. Architecture now is looking at excessive means and excess in general, and the whole paradox is going to have to change once the Coronavirus is over.

BEST PARKING LOT, 1977, model overview

BEST PARKING LOT, 1977, model overviewFredy Massad (FM)- Do you think this is a good moment to change the way things are happening? Rem Koolhaas’ exhibition in the Guggenheim already talks about moving out to the countryside and the countryside being the future. This move, you have mentioned, brings another set of new problems.

JW- For every argument, like the argument for tall buildings, there will be a problem as a consequence. For example, the success of the city as an idea attracted, by today’s estimates, almost 80% of the world’s population to live in them. Now, suddenly, there is this new rush to the suburbs which is equally damaging, if no more so, from an ecological perspective. In terms of environmental interest, suburban growth and suburbia have always been the enemy. Architectural criticism for the last 30 years has been against the proliferation of suburbia because it takes too much energy and it ruins land; it consumes territory, consumes forest, consumes vegetation. Changing the paradigm is going to take an awful lot of thinking. Changing the way we live, if you are looking at architecture through this perspective, is going to take a lot of thinking and a lot of effort, as well.

MQ - Maybe I can pick up on a word that you just used: “vegetation.” In your projects in the late 70s and 80s you truly conceptualized using vegetation as an architectural material. I think that attitude shows an incredible economy of means; vegetation is free, quickly grows into building mass and performs well in many aspects that go beyond the environmental. But nowadays it seems that vegetation is used, more often than not, to green-wash urban projects and buildings. And the technologies that are implemented to introduce vegetation in buildings are extremely expensive not only in terms of cost but also in terms of energy consumption...

JW- That is what I have always said. We are turning vegetation into décor. Designers are using vegetation just because it makes architecture look green. It is like that funny cartoon said “why don’t we just paint our buildings green?” I think that if a project is in an environment with lots of trees and vegetation, you should keep it - at least as much as humanly possible. That is mainly what we did with our projects. A few of them are green, green buildings. Also, why do you have to always spread parks by land? Why can’t we build parks upwardly? We should enjoy the parks in the sky just as we enjoy them on the land.

I guess that what I am really saying is that we have a lot of thinking to do. That was the nice part of SITE in the early days. We always sat around a lot to talk and really discussed options and values and self-criticism. Self-criticism is the hardest of all. Going back to Kiesler, he said one day “James, you are making all these architectonic sculptures but you know, they are abstract art. Abstract art is dead, that is old fashioned.” I said “well, everyone does something that is probably already dead!” Kiesler was a really harsh critic but he was this incredible person to listen to, talk to, because he believed in the integrated arts. He really believed in the fusion of art, architecture, context, vegetation, which is something he imparted to me and I have spent my life believing that it is right. The more integrative a thing is, usually the better it is and the more information there is.

MQ - In the past you have also used the word frugality, which I think could be instrumental to our current times... the term is close to economy of means but it seems to carry a different meaning, imply a different attitude, somehow it is seems less tactical and more profound...

JW- I think it was Picasso who said that constraints are great because you cannot foresee how inventive you will become when you use that as your starting point. And that is really true. It really is true. Even with the early BEST buildings, the client was not going to spend a lot of money doing them. We had to think of something that was intrinsic to the context, something that would make people think or talk or wonder and we had to do it with practically no money. Frugality is a very good word these days, I agree. I think the problem in the architectural profession is that many bad habits come from the paradigm of excess and nobody wants to give them up. Nobody wants to do the necessary rethinking because it is going to be a painful process, there is no question about it. But I think the younger generation are going to do it.

MQ - I also found, in one of your older texts, what I thought was a rather interesting architectural plot twist: “we need to go from form, space and structure to idea, attitude and context”. Do you still think that?

JW- I still believe that. It is interesting how once you say something, like I am saying today, people hold you to it for the rest of your life! There are buildings that we have done that are very functional. In fact, they all were and most of the time the economy was driven by that functionality, by their simplicity. But still I always found, having a collage sensibility in my mind, that almost everything can be added to any context. If you have an idea, and a certain attitude, then the context usually gives you the information you need. With the parking lot project, there were cars and asphalt, and that was all we had. That is what we worked with. You do not want to build a huge bronze sculpture. Thinking that way, but not letting it destroy your creativity, I think that is the catch.

A lot of people use economy in not such great ways. For example, Sixth Avenue is probably the worst place in the world. Upper Sixth Avenue has more bad buildings than anywhere I can think of. They are all built on a Miesian idea but none of them have Mies’ proportions or concepts. None of that. They are just sleek, glass buildings. They are awful. When I think about my life, living in New York, unless I had an appointment, I would never go to Upper Sixth Avenue. I would never go there for pleasure; I would never go there for any other reason. A part of a city should not look like that. It is like everything else, there are parts of the city that have been wonderfully thought and other parts that are very hostile.

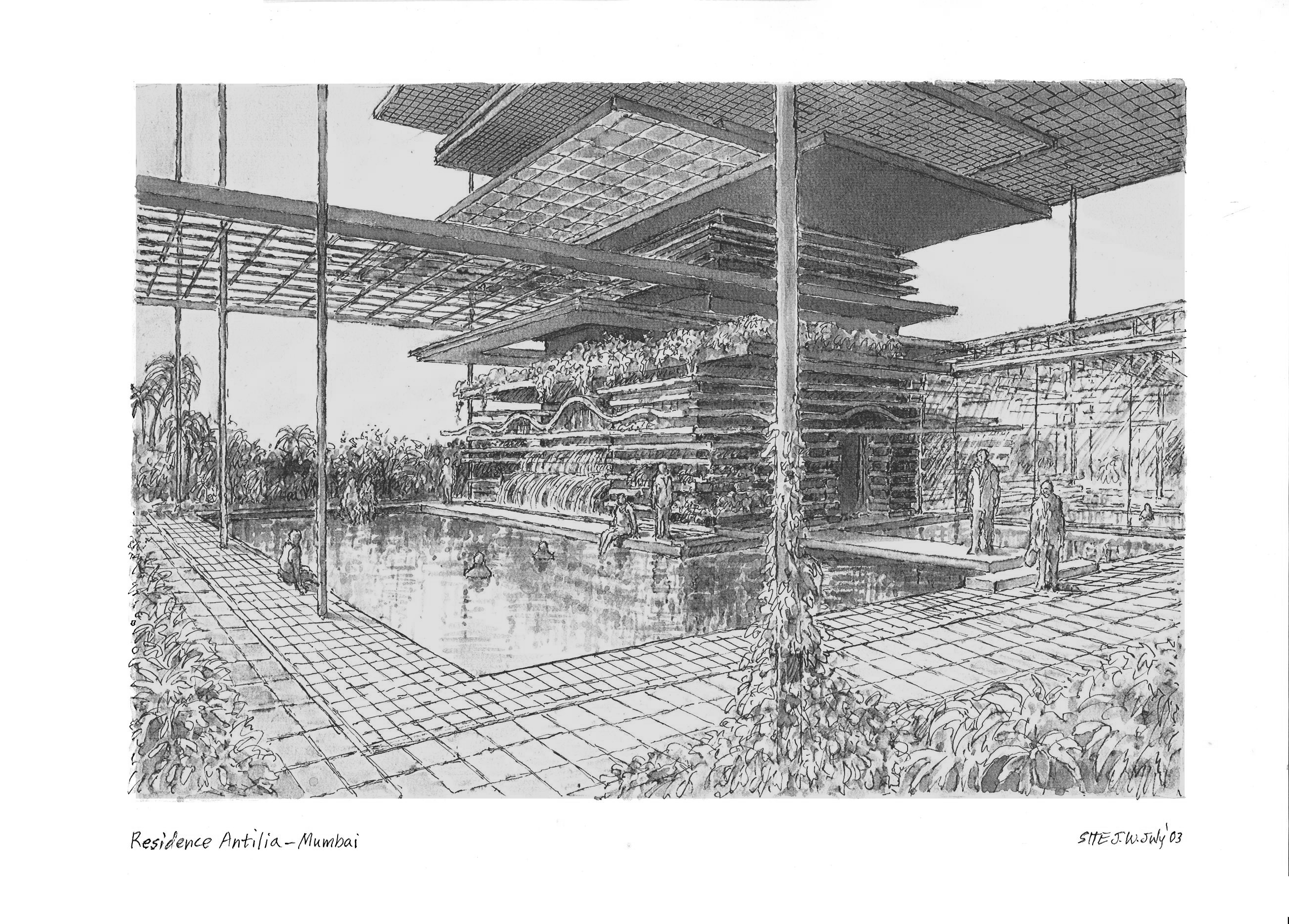

RESIDENCE ANTILIA, 2003

RESIDENCE ANTILIA, 2003Álvaro Rojas (AR) - Can I ask a question then? What do you think about Brasilia then, James?

JW- I never liked it that much, not even in school. It is derivative of Le Corbusier without understanding what Le Corbusier was about as an artist. It is a “Corbusier-esque” complex, but so spread out and so grim, that it resisted people. It resisted occupancy. But interestingly, people started adapting to it. They inserted their own ideas into it and it became enriched; similarly to the theory behind the High Rise of Homes, it became enriched by people’s additions. It became quite livable and a hospitable place after time. That is an interesting story. And that will not happen to Upper Sixth Avenue, it is hopeless. You cannot do anything. At least in Brasilia there was a possibility for insertion, for adaptation and changing.

AR- I am not sure if you have been to Brasilia but I believe you will find it to be a horrendous experience. I actually prefer Upper Sixth Avenue.

JW- Well, I only went there once but when I got there, there were lots of interventions, there were lots of things. But yes, the overall thing, the overall concept, is just awful. It is. And it is a good demonstration of what imitation of someone else’s talent is, without understanding those talents at all. That is exactly what it is. It is an imitation of Le Corbusier without any understanding of Le Corbusier. It is really fascinating.

FM- Talking about monumental architecture, the age of the star-architects and iconic buildings, do you think they are solely the celebration of global capitalism? What do you think our period is a consequence of?

JW- It is a difficult question because, historically, monumental were the civic or religious buildings, and they all had iconography. They had symbolism, they had sculpture on their surfaces, they had a rich reservoir of materials and ideas to include that were not oppressive or overwhelming. The reason Brasilia looks so awful is because there is no iconography, there is nothing to read. Just compare it to the Chartres Cathedral, there we are talking about one of the most readable buildings in the world. I always say that Chartres Cathedral is the most functional building in the world. It achieves exactly what it went out to achieve in the first place. It wanted to communicate, it wanted to overwhelm you with the power of the Lord, it wanted to impress you, it wanted to make you think. Actually, it is much more functional than a Miesian building in many ways

MQ- James, your comment comparing Sixth Avenue and Brasilia made me think about this editorial project and its ambition to have global scope and impact. It is really interesting because these two worlds – never mind others – seem to move at a completely different speed and to be administered by a completely different set of rules. Interestingly, today, the Russians claimed to be the first to have a working vaccine against the Coronavirus. It is speculated that the only reason they could have done it this fast is, of course, by avoiding the legal hurdles and international controls that govern the rest of the initiatives. This is a dangerous example, but it did make me think that there is something thought-provoking about developing and testing alternatives to a problem and the relationship it has to diverse cultural and political systems.

JW- What you are doing is bringing up all issues. We are still discussing what to do on matters that need a lot of attention and I do not know what the solutions are. I have no idea, sitting here today, what I would do if I had to do a City Hall or the White House. I have no idea where I would start because I do like to communicate and most of the things that I have been involved with have lent themselves to that kind of communication. What, for example, would Marcel Duchamp done for a social mural given his commitment? He would have to do some kind of funny inversion and I think I would do the same thing. There is something ridiculous about politicians and governments anyways, but I am also sure that no civic organization wants to be joked with or made fun of...

MQ- ...with their own money, on top of that…

JW- I know; it is just hard. It really is very difficult. I feel more dedicated to the world of Oscar Wilde than I do of Shakespearean tragedy. There are different worlds and we occupy them to the extent that our talents allow us to. But I think a lot of architects do not care. They just have all the clichés in the bank. I think that is the excuse for these massive buildings shaped like a corkscrew. I will keep saying it: “no sculptor on earth would make some of those shapes, they are just so awful.” And yet architects jump right in. No abstract artist would do that kind of thing. It was not that great when it was going strong, and it is even less great now. It is less inclusive. Like the Henry Moore in the plaza.

MQ- That is funny... I actually live in Toronto and they just moved a Henry Moore to a plaza.

JW- When in doubt, put a Henry Moore in the plaza! It is so meaningless. You have this big amebic shape sitting there on a box or in a pool. You are starting something that I think has a great promise. Because forcing people to think in the first place is one thing, you have to do that. Opinions and solutions are two different things. I am sitting here giving opinions, but I do not have a solution to some of your best questions.

AR- I like your apprehensions that you just mentioned about how to think a project or a city. How do you do it, as you said before, conceptually, how do you respond environmentally, so on and so forth. I think that the problem with architects is that most do not think about those issues, they do not have those apprehensions that you just mentioned. That seems to be the problem. And for most architects, and you mention this all of the time, the only concern is the form and shaping.

JW- Yes, absolutely. For whoever worked on Chartres Cathedral, that was not the only thing they had in mind. It is unbelievably complex. Architectural, creative, humanitarian, ethical, religious, social, all kinds of issues in mind. That is what makes it so eternal. I remember going to Chartres for the first time, you cannot help but have a religious experience. It overwhelms you, it is masterly conceived and over an extended period of time. You mentioned time to think? I think the Cathedral is that good because it was thought over a long period of time and they kept bringing on the good ideas. But I do not think we currently have much time. Given the coronavirus, and the nature of cities and suburbs, no, I am not sure how much time nature is going to graciously give us. National Geographic keeps calling us the “scourge of the earth.” We are the scourge of the earth. And the earth is going to fight back, it always does. And there have been civilizations that have disappeared and old species that have disappeared. There have been entire revolutions in the earth’s history. We may be the shortest one of all, given our inclinations. It is ironic because we can in fact think amazing things. The genius of the human brain is just mind-boggling. I always quote some anthropologists and scientists that were talking on a TV show about the human brain and one of them said “the problem of the human brain is that the gap between the brain of an Einstein and an average human being is much greater than the average human being and a dog”. And it is true beyond belief! And we have witnessed it with the Trump generation. The Trump generations is proving that it is an absolute fact, not a supposition. I cannot believe that people actually value the things he says and does. They are so stupid and so mindless that you cannot believe that a standing human being could say them. I personally feel he is naturally deranged. I do not know why more psychiatrists do not go after him. Now I am talking about my least favorite subject.

FM- We are talking about all these subjects but one of the most successful buildings in New York is Calatrava’s building. What is your opinion about his train station?

JW- Well, I am not sure. Again, it is that kind of shape making thing but it does not make me think. If I did that as a table top sculpture you would hate it. He does it as monumental architecture, and there it is. It is actually funny because it is right where our office was and we looked at those big points every day. I guess that the only thing that sort of works about it is that big open space inside. But I have heard that even the enterprises that have joined, all those posh stores, are not doing very well. Good news is that is so far to walk, it is so spread out, that all of this is probably good for social distancing. Maybe its singular greatest contribution is social distancing.

AR- It was ahead of his time!

JW- He is ahead of his time, yes! He says that. Our world, the thinking world, has a lot of thinking to do.

MQ- Now, that is an instant motto; “Our world, the thinking world, has a lot of thinking to do.” We will hold you to that.

JW- You can quote that one. But it really is. I am so glad you are doing this. I think having a concise dialogue of this nature will start to produce good ideas. I had a dialogue with Dan Wood, who also does not build giant structures but he is doing a lot of remedial work. Taking existing situations and improving upon them. Making them better. I think innovation and remedial architecture is going to be a big field. I think that the emphasis, or were the money is going to be spent, is going to shift around. But remedial is not handling what we already have. I mean, we have a lot of buildings that are pretty unlivable and are not going to rent if people move out. And how do you get rid of them? How do you get rid of some of the new buildings in New York? The World Trade Center is just awful. That is really one example that no self-respecting sculptor would do. I think it is so bad as a shape, so trite, that you cannot conceive somebody doing that. And it is a giant edifice with a giant space inside. Even the original World Trade Center had to be taken over by New York State offices because it never rented efficiently. Think about it, the original World Trade Center did not rent sufficiently, it had to be patronized, basically, by New York State offices. What we are going to do with this thing now? Some of these big questions arise from the madness of developers, or the madness of big money or money itself in excess, and they are really going to have to face the music. They are really going to face some very critical questions. You cannot tear down these buildings easily. Demolition is probably for smaller buildings. I do not know how you demolish a building like that. In a way, the original World Trade Center was demolished, miserably, but this one, if it does not rent and it is not profitable, what do you do with it? They talk about urban farming, but so many buildings are built that they would not be in any way useful for that kind of transformation. I have always been a little suspicious of urban farming because, from what I know about farming, it is so complex and seasonal, and so reliant on rain and sunshine, that I do not see it working very well in a city. And especially in a city under the shade of skyscrapers. There are a lot of thing like these, an almost endless session of subjects we could talk about that need thinking. Anything you want to talk about, I am willing at least say something.

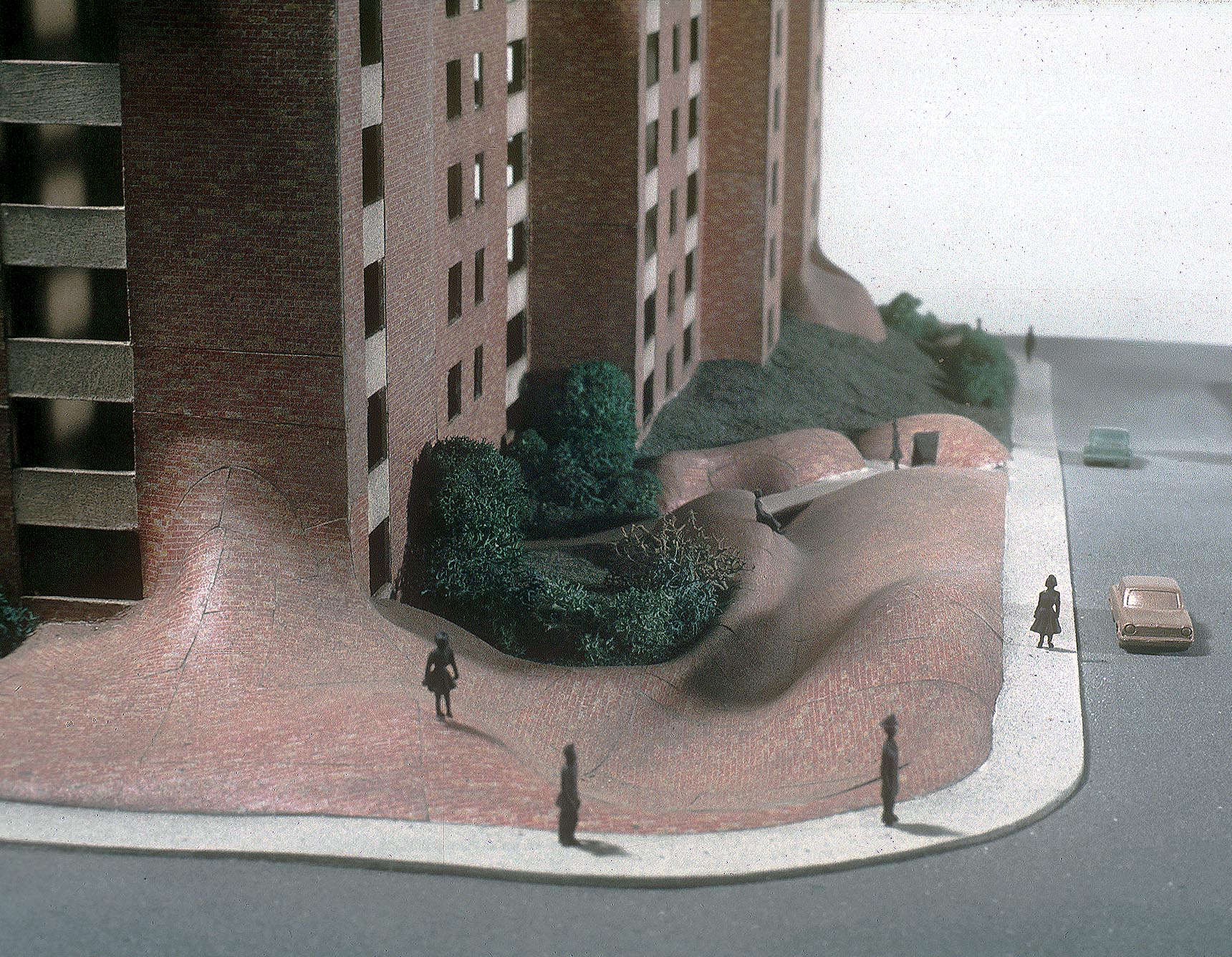

Peekskill Melt Apts model, 1971

Peekskill Melt Apts model, 1971AR- I just wanted to perhaps, tempt you James to say a few words about your friendship with Michael Sorkin, whom we all knew and loved.

JW- Michael was an awful lot of brain. He certainly had one. He was the Einstein of this vision, I guess. I miss him terribly. I miss him every day. We were always coming to each other, having dinner together, doing something. He was definitely interested in urban centers and was part of that generation that considered them as a much better solution to suburbia. I believe that in this post-pandemic world he would be changing his mind. He advocated with building tall buildings, but he also advocated with public space and cities with much great variety. That was the main thing he advocated for and the area we agreed on. This was not necessarily about economy of means, because it depended on being committed to a big development. But in terms of big development, he was certainly the most humanistic of all, beyond any developer I have ever met. I wish he would live, if for no other reason, just to realize some of his dreams and some of his projects have him a victim of this pandemic. It is such an irony because he believed in clustering and people coming together, meeting in public spaces, having conversations; he truly believed in that. It is a cruel act of history that he perished as a result of his conviviality and his nature. If Michael had lived how would he have changed his mind?

MQ- James, maybe to wrap up we can go back to the first question. Given the arch of your professional experience and the crises that you have witnessed, do you think we are living a “this too shall pass” moment, or do you think we are facing the greatest challenges ever?

JW- I think this is a sink or swim moment, especially if we do not do something pretty fast. That is for sure. It is written on the wind. I think that is inevitable. My life has been paused, basically. Everything on our office is stopped. Everything that was on the drawing board, or prospects, have all been stopped or suspended. And I would assume every office is having that problem. Ours probably more than others because our main product is aesthetic and aesthetic is not lifesaving. But I do not want to think of myself as irrelevant because it will come back. It is interesting how much of culture is still plunging on because people absolutely need it. Without culture our psychologies would collapse. We have to perform, dance, sing, paint, sculpt. It is in our DNA. But I do not want to do it on a suicidal basis, I do not want to achieve social aesthetics and do it with the kind of buildings that are just absolutely absurd. The last ten years more absurd buildings have been built than ever before. They are incredibly difficult to maintain, incredibly difficult to use. I still think that the best used spaces are literally big boxes. Phillip Johnson said that, going through all of history, the best spaces, the ones that are continued to be used forever, are literally big boxes. Chartres Cathedral is a good example of a big box.

We should all remember that Shakespeare’s times saw the most pandemics and they were evidently catastrophic. And yet, they produced Shakespeare. They produced middle age art, churches. There were still incredible things being done. I just hope we are as smart once again .

Interview date: 12 August, 2020