Mondo Nomada

Text by

Manuel M. Vela

PhD. in Fine Arts by the University of Granada. As an artist he has been awarded in prestigious national competitions: Caja Castilla La Mancha Prize, FOCUS Foundation, Rafael Zabaleta, etc. His work is represented in private and public collections such as the Museo del Grabado Español Contemporáneo, Diputación de Jaén, Calcografía Nacional, Universidad de Granada, etc.

In 2017, he published La Alhambra con regla y compás. El trazado paso a paso de alicatados y yeserías (Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife / Editorial Almizate) with versions in Spanish, English and French, and 24 Patrones para dibujar la Alhambra (Editorial Almizate) with versions in Spanish and English. In September 2019 his latest book El Real Alcázar de Sevilla con regla y compás (Editorial Almizate) has been published, also with versions in Spanish and English

NOMADIC GEOMETRY

One quality of Islamic geometric decoration is its permanent movement. This manifests itself in two ways. On the one hand, in regard to the structure of the compositions, and on the other, to its diffusion throughout places, sometimes very distant from each other. Regarding the first aspect, the kaleidoscopic character of many compositions, forces the spectator to go through them without being able to gaze at a specific point. Diverse centers of attention and the repetition of shapes, with rhythms that are not always easy to discover, endow Islamic art with a dynamism that contrasts with the apparent static quality of the plastic resources shaping them. Endless lines traverse the contours of polygons intertwining with each other in visual labyrinths, while bright colors fill the internal spaces. Nothing is permanent, and if it came to be, light appears to deny it. In a space like the Sala de las Dos Hermanas de la Alhambra, this phenomenon is more than obvious. To the varied geometric decoration on its walls, which include tiled plinths and stucco reliefs, is added the light which penetrates through the windows and above which floats the splendid muqarnas vault, making nothing permanent, veering as the hours of the day go by.

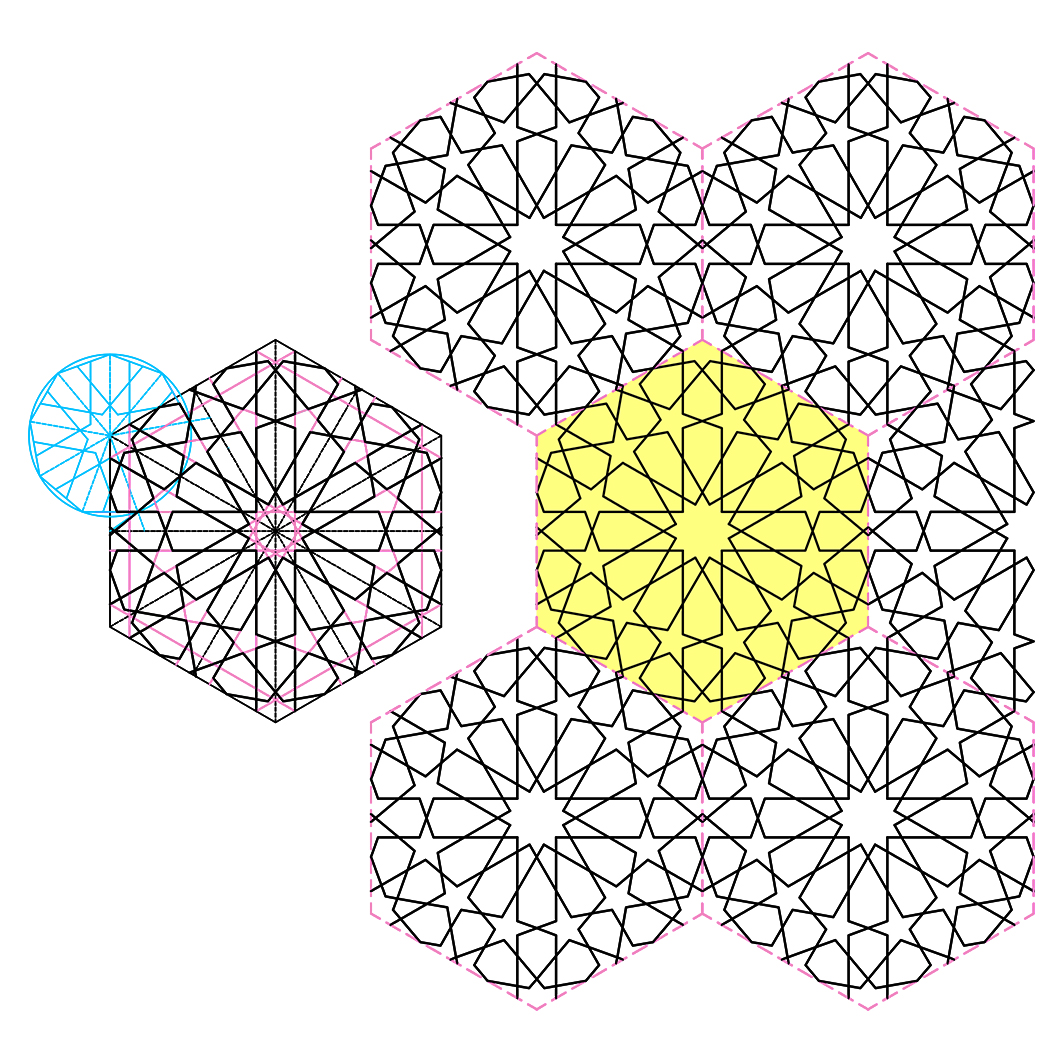

But movement also manifests itself in the physical displacement of the geometric designs between one place and another, in different times. Designs or patterns whose genesis is in the East traveled to Magreb or Al-Andalus, while others moved the opposite way. The origin of all of them is not always certain. The same design may even have been developed in two different places. It must be taken into account that parting from modular grids, some simple and some more complex, there are many possibilities that two masons, without knowing each other, could achieve the same solution in far away places. But artisans would also travel, and if not them, their products would. Factories and workshops exported fabrics, ceramics, furniture, books, etc. and this way, many designs materialized in diverse forms, would be disseminated.

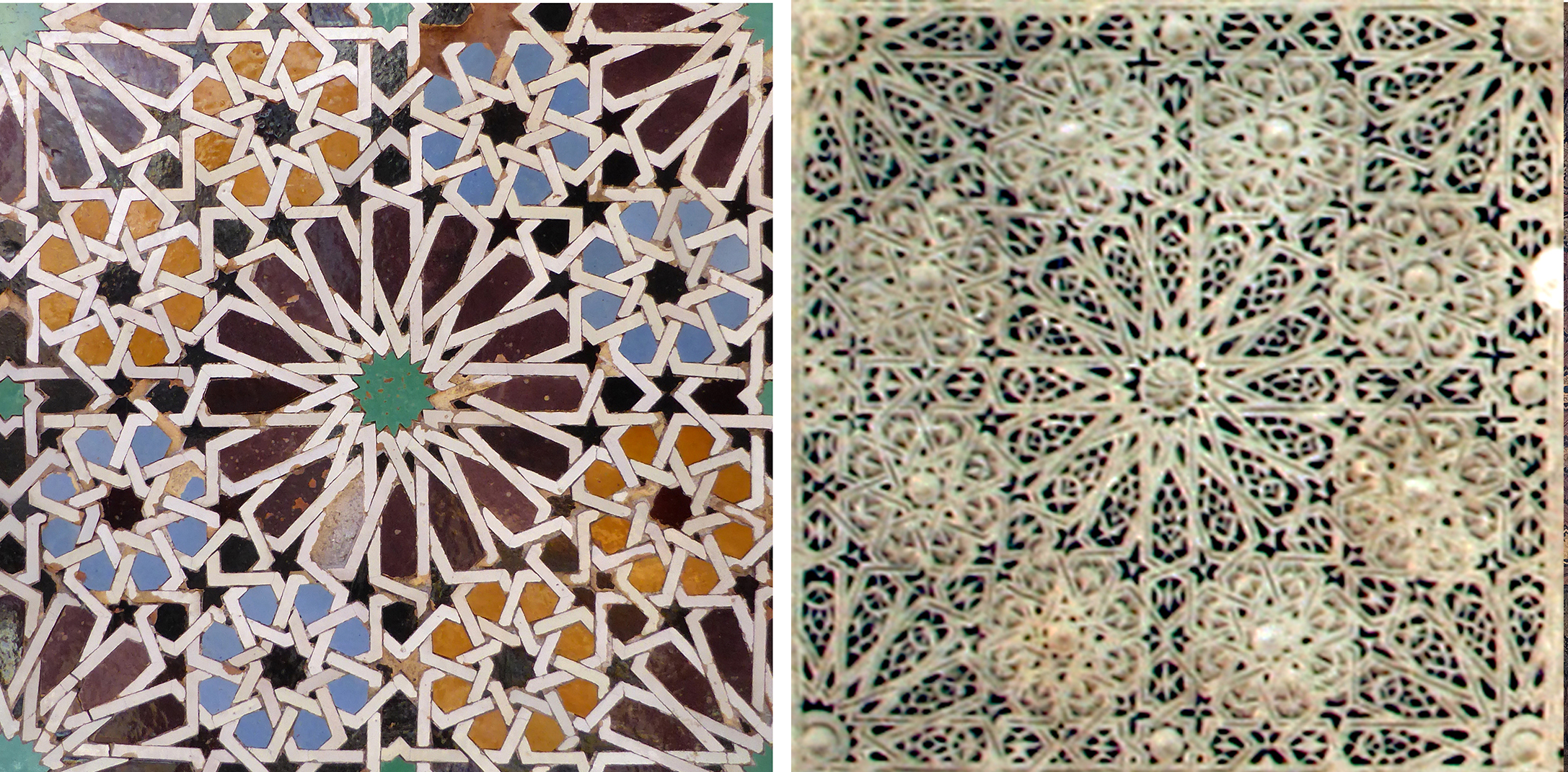

Amongst the abundant examples of travelling designs that we can find in the Alhambra; I have selected two. These are two tiles, one in the previously mentioned Sala de las Dos Hermanas and the other in the adjoining Mirador de Lindaraja. We can find examples of both in other places, some more or less close, and executed in different materials, like ceramic, wood or plaster. You can almost always find small variations between one and other that enrich the design, even if the geometric base is the same.

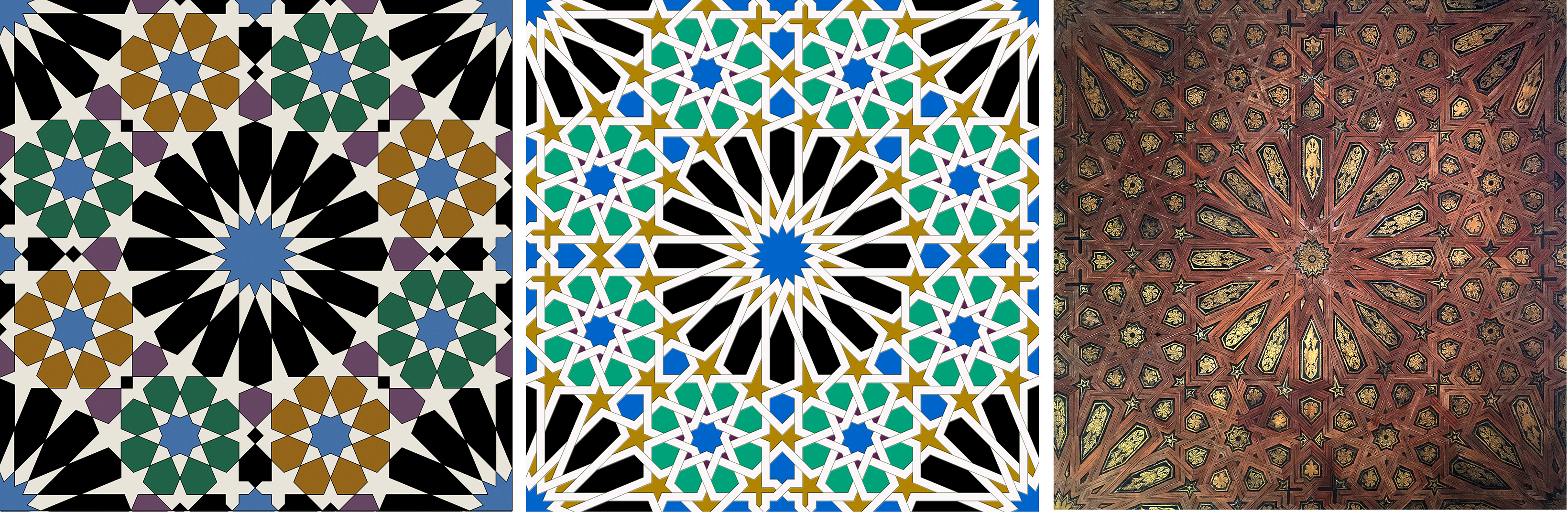

1 2 3

1 2 3

4 5

Of the five examples in the upper illustration, the first one belongs to the jambs of the arches that make way to the lateral alcoves of the Sala de las Dos Hermanas. In it, one can clearly see the linear scheme of the composition on which the other four are based. It is made up of four wheels with sixteen arms (zafates) surrounded by other eight that serve as a link or union between them. While the shapes in the first are juxtaposed, sharing contours, in the other four a more or less wide band serves as a separation. The genesis of this design may have been in the Alhambra itself, and it would be dated to the mid XIV century1. This combination of wheels or rose windows of eighteen and eight appears in the basic layout of the coffered ceiling of the Hall of Comares, and later, in the plinths of the Sala de las Dos Hermanas (1), which is part of de Palacio de los Leones built by Muhammad V towards the end of the XIV century, or the plinths of Mexuar (2), an area in the Alhambra that has undergone many reforms, and can´t be dated with certainty. Some authors believe they proceed from the disappeared Hall of the Helias, in the southern area of the Palace of Comares, from which they were moved during the XVI century, but there is also evidence of the intervention from some Sevillian ceramists, the Polido brothers, though there is no concrete certainty to what their contribution may have been. The small differences in the proportions of some of the motifs that are repeated in some walls may indicate Nasrid or Christian origins in some part of these plinths.

In video nº 7 of my YouTube channel I explain step by step the geometric layout of this design

Another roofing in which this same geometric motif is present is the one covering the entrance hall in the Patio de los Arrayanes (3). In this one, the band becomes wider, as it corresponds to the taujeles or strips that make up the layout. The interior spaces appear decorated with renaissance drawing in gold leaf, which reveals, like the text in Gothic character that runs through the arrocabe, an intervention from the times of the Catholic monarchs.

In North Africa, where the reciprocal influences between Merini and Nasrid where constant, this theme appears once again in constructions like the Madrasa Bou Inania of Meknes, where it is found in plasterworks from the mihrab (5). A little further south, in Marrakesh, the Saadian tombs (late XVI) include it among the designs of their tiling (4). These are similar to the ones I the Mexuar of the Alhambra, but they present small variations in some aliceres, and above all, the color range.

The Mexuar tiling served as model for the design of the plinths of the Moroccan Court, in the Metropolitan Museum of New York, built in 2011 by Moroccan artisans. This is the center of the space destined to the important collection of Islamic Art of the museum. It recreates a courtyard with an Andalusian setting, where, next to Alhambra inspired plinth, four original Nasrid columns (XIV century) support the plaster arches and the wood carved eaves.

1. MALDONADO PAVÓN, Basil. (1989), The Hispanic-Muslim art in its geometric decoration. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Madrid. (pp. 303-307)

Granada, November 2020